HQ Team

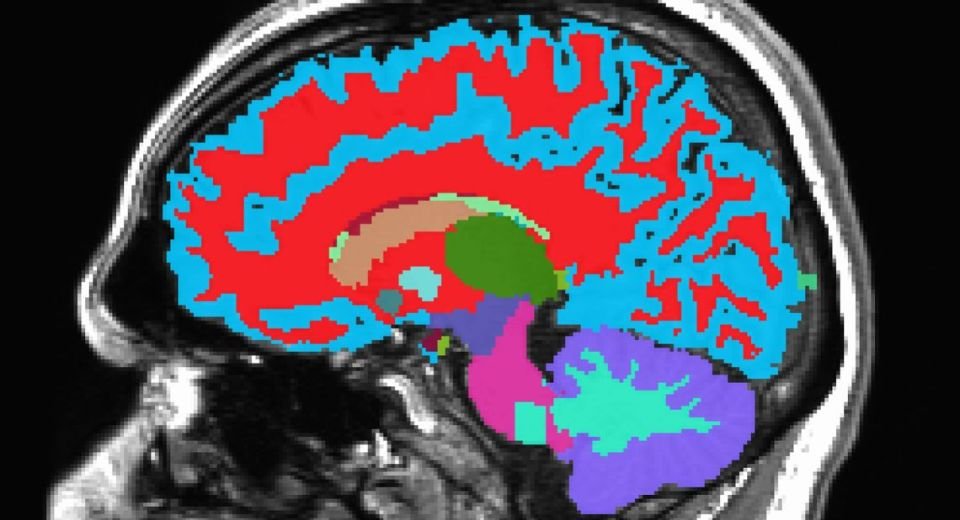

July 7, 2025: Scientists can tell how fast or gracefully you are ageing from a single magnetic resonance image of your brain, according to researchers at Duke University.

The tool can estimate your risk in midlife for chronic diseases that emerge decades later and can help motivate lifestyle and dietary changes that improve health, according to a statement.

“The way we age as we get older is quite distinct from how many times we’ve travelled around the sun,” said Ahmad Hariri, professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University.

The snapshot of the brain in older people can predict whether someone will develop dementia or other age-related diseases years before symptoms appear.

“What‘s cool about this is that we‘ve captured how fast people are ageing using data collected in midlife,” Hariri said. “And it’s helping us predict the diagnosis of dementia among people who are much older.”

‘Ageing clocks’

Algorithms of “ageing clocks” rely on data collected from people of different ages at a single point in time, rather than following the same individuals as they grow older, he said.

The challenge was to come up with a measure of how fast the process was unfolding, “that isn’t confounded by environmental or historical factors unrelated to ageing.”

Researchers gleaned data from 1,037 people who have been studied since birth as part of the Dunedin Study, named after the New Zealand city where they were born between 1972 and 1973.

Every few years, Dunedin Study researchers looked for changes in the participants’ blood pressure, body mass index, glucose and cholesterol levels, lung and kidney function, and other measures — even gum recession and tooth decay.

They used the overall pattern of change across these health markers over nearly 20 years to generate a score for how fast each person was ageing.

Dunedin study

The new tool, named DunedinPACNI, was trained to estimate this rate of ageing score using only information from a single brain MRI scan that was collected from 860 Dunedin Study participants when they were 45 years old.

The researchers used it to analyse brain scans in other datasets from people in the UK, the US, Canada and Latin America.

Across data sets, they found that people who were ageing faster by the tool’s measure performed worse on cognitive tests and showed faster shrinkage in the hippocampus, a brain region crucial for memory. They were also more likely to experience cognitive decline in later years.

Researchers also examined brain scans from 624 individuals ranging in age from 52 to 89 from a North American study of risk for Alzheimer’s disease.

Those who the tool deemed to be ageing the fastest when they joined the study were 60% more likely to develop dementia in the years that followed. They also started to have memory and thinking problems sooner than those who were ageing more slowly.

‘Our jaws dropped’

When the team first saw the results, “our jaws just dropped to the floor,” Hariri said.

People whose DunedinPACNI scores indicated they were ageing faster were more likely to suffer declining health overall, not just in their brain function, and were susceptible to cardiovascular diseases.

“The link between the ageing of the brain and body is pretty compelling,” Hariri said.

People worldwide are living longer. In the coming decades, the number of people over age 65 is expected to double, reaching nearly one-fourth of the world’s population by 2050.

Dementia’s economic burden is already huge. Research suggests that the global cost of Alzheimer’s care, for example, will grow from $1.33 trillion in 2020 to $9.12 trillion in 2050, comparable to or greater than the costs of diseases like lung disease or diabetes that affect more people.

The team hopes the tool will be of better help than ageing clocks, based on other biomarkers, such as blood tests, can not.

The new tool will also help scientists better understand why people with certain risk factors, such as poor sleep or mental health conditions, age differently, said first author Ethan Whitman.

The authors have filed a patent application for the work, which was published July 1 in the journal Nature Aging.