HQ Team

June 23, 2023: Australian researchers have unearthed the process of how an infectious virus enters human cells from animals.

The researchers at the University of Queensland uncovered the structure of the fusion protein of Langya virus that affected a cluster of people in China in August 2022.

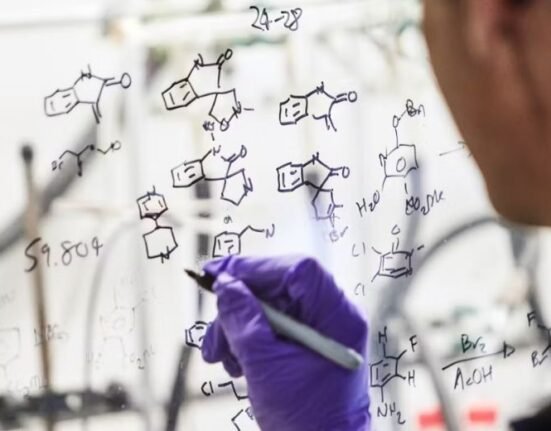

The team used a molecular clamp technology to hold the fusion protein of the Langya virus in place to uncover the atomic structure using cryogenic electron microscopy at the university’s Centre for Microscopy & Microanalysis.

The research was published in Nature Communications.

The Langya henipavirus, also known as Langya virus, is a species of henipavirus first detected in the Chinese provinces of Shandong and Henan. the virus caused fever and severe respiratory symptoms and was from the same class of viruses as the deadly Nipah and Hendra viruses.

Spillover events

Henipaviruses, to which Langya belongs, are regarded as the most lethal paramyxoviruses, with a case fatality rate of about 70%.

The Henipaviruses emerged in the 1990s and numerous spillover events of the virus from bats to horses have occurred in Australia, resulting in several human exposures.

The Nipah virus spillovers to humans occur almost annually in Bangladesh, and several outbreaks have also been recorded in India and the Philippines.

In recent years, the Henipaviruses genus has expanded significantly, with new viruses discovered in Africa, Australia, Asia, and South America, according to the researchers.

Cedar virus

The new viruses include Cedar virus, isolated from flying foxes in Australia, Ghana virus, isolated from bats in Africa, Mòjiāng virus, sequenced from rats in China, and Gamak & Daeryong viruses, discovered in shrews in the Republic of Korea.

Langya virus was identified in a throat swab from a human patient in China. Outside of Nipah and Hendra, Langya is the only other Henipavirus that is known to infect humans. However, it is suspected that Mojiang and Ghana viruses also possess pathogenic potential.

“We’re at an important juncture with viruses from the Henipavirus genus, as we can expect more spillover events from animals to people,” Dr Ariel Isaacs at the University of Queensland, said.

“It’s important we understand the inner workings of these emerging viruses, which is where our work comes in.”

Associate Professor Daniel Watterson, a senior researcher on the project, said the researchers also saw that the Langya virus fusion protein structure was similar to the deadly Hendra virus, which first emerged in southeast Queensland in 1994.

Hendra virus is a bat-borne virus that is associated with a highly fatal infection in horses and humans.

Potential to get out of control

“These are viruses that can cause severe disease and have the potential to get out of control if we’re not properly prepared,” Dr Watterson said.

“We saw with COVID-19 how unprepared the world was for a widespread viral outbreak and we want to be better equipped for the next outbreak.”

Understanding the structure and how it enters cells is a critical step towards developing vaccines and treatments to combat Henipavirus infections, Dr Isaacs said.

“There are currently no treatments or vaccines for them, and they have the potential to cause a widespread outbreak.”

The researchers will now work to develop broad-spectrum human vaccines and treatments for Henipaviruses, such as Langya, Nipah and Hendra.

Shrews

Langya virus does not seem to spread easily among people. However, researchers are of the opinion that as shrews serve as a reservoir, they can transfer the virus between themselves and could infect people directly by chance or through an intermediate most.

Henipaviral diseases are listed on the WHO list of priority diseases that require exigent research into vaccines and therapeutics.

This is largely due to the high associated case fatality rate and the global migratory patterns of the fruit bats, which act as the main animal reservoir for Henipaviruses.

The researchers said there was a clear need for improved vaccine preparedness against these emerging pathogens.