HQ Team

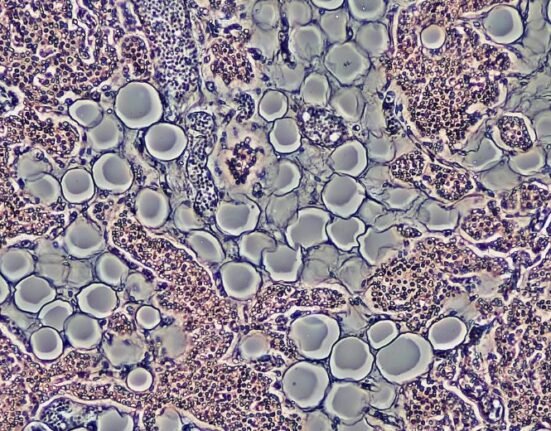

November 24, 2023: A bacterium, staphylococcus aureus, single-handedly imbalances the equilibrium of micro-organisms, that keep the skin healthy, and cause itching, according to researchers at Harvard Medical School.

The bacterium (plural is bacteria) sets in motion a molecular chain reaction by activating nerve cells in the skin that results in the urge to scratch.

It releases a chemical that activates a protein on the nerve fibres that transmit signals from the skin to the brain.

Until now the itch that occurs with eczema and atopic dermatitis was believed to arise from the accompanying inflammation of the skin.

“We’ve identified an entirely novel mechanism behind itch — the bacterium Staph aureus, which is found on almost every patient with the chronic condition atopic dermatitis,” said senior author Isaac Chiu, associate professor of immunology at the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School.

“We show that itch can be caused by the microbe itself.”

Eczema, atopic dermatitis

The research adds a new dimension to the long-standing puzzle of itch and helps explain why common skin conditions like eczema and atopic dermatitis are often accompanied by a persistent itch.

Treating animals with an FDA-approved anti-clotting medicine successfully blocked the activation of the protein to interrupt the key step in the itch-scratch cycle. The treatment relieved symptoms and minimised skin damage.

The results, after studies in mice and humans, can lead to the design of oral medicines and topical creams to treat persistent itch that occurs with various conditions linked to an imbalance in the skin microbiome, such as atopic dermatitis, prurigo nodularis, and psoriasis.

“Itch can be quite debilitating in patients who suffer from chronic skin conditions. Many of these patients carry on their skin the very microbe we’ve now shown for the first time can induce itch,” said study first author Liwen Deng, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Chiu Lab.

Researchers exposed the skin of mice to the bacterium. The animals developed an intensifying itch over several days, and the repeated scratching caused worsening skin damage that spread beyond the original site of exposure.

Alloknesis

The exposed mice were more likely than unexposed mice to develop abnormal itching in response to a light touch.

This hyperactive response, a condition called alloknesis, is common in patients with chronic conditions of the skin characterised by persistent itch. But it can also happen in people without any underlying conditions — think of that scratchy feeling you might get from a wool sweater.

The team focused on 10 enzymes known to be released by this microbe upon skin contact. One after another, the researchers eliminated nine suspects — showing that a bacterial enzyme called protease V8 was single-handedly responsible for initiating itch in mice.

Human skin samples from patients with atopic dermatitis also had more S.aureus and higher V8 levels than healthy skin samples.

The analyses showed that V8 triggers itch by activating a protein called PAR1, which is found on skin neurons that originate in the spinal cord and carry various signals —touch, heat, pain, itch — from the skin to the brain.

PAR1 protein awakening

Normally, PAR1 lies dormant but upon contact with certain enzymes, including V8, it gets activated. The research showed that V8 snips one end of the PAR1 protein and awakens it.

Experiments in mice showed that once activated, PAR1 initiates a signal that the brain eventually perceives as an itch. When researchers repeated the experiments in lab dishes containing human neurons, they also responded to V8.

“When we started the study, it was unclear whether the itch was a result of inflammation or not,” Deng said. “We show that these things can be decoupled, that you don’t necessarily have to have inflammation for the microbe to cause itch, but that the itch exacerbates inflammation on the skin.”

The PAR1 blocker is already used in humans to prevent blood clots and could be repurposed as anti-itch medication.

“Why do we itch and scratch? Does it help us or does it help the microbe? That’s something that we could follow up on in the future,” Deng said.