HQ Team

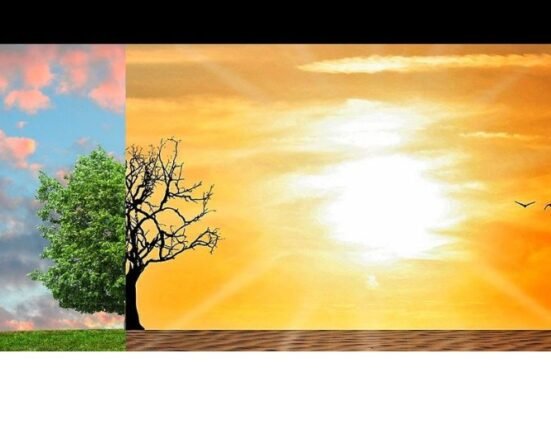

September 5, 2023: South American forests had lost their ability to store carbon and were releasing it into the air due to an El Niño climate event which resulted in hot temperatures and drought eight years ago.

The forests were unable to function as a carbon sink during the 2015-2016 period when El Niño hit the region leading to high sea-surface temperatures in the Pacific Ocean, according to a study.

Researchers led by Dr Amy Bennett, a Research Fellow at the University of Leeds, said a similar event is underway now.

“Tropical forests in the Amazon have played a key role in slowing the build-up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere,” said Dr Bennett, from the School of Geography at Leeds.

“Scientists have known that the trees in the Amazon are sensitive to changes in temperature and water availability, but we do not know how individual forests could be changed by future climate change.

Amazon, Atlantic forests

“Investigating what happened in the Amazon during this huge El Niño event gave us a window into the future by showing how unprecedented hot and dry weather impacts forests.”

The study brought together the RAINFOR and PPBio research networks, with dozens of short-term grants enabling more than 100 scientists to measure forests for decades across 123 experimental plots.

The plots span Amazon and Atlantic forests as well as drier forests in tropical South America.

These direct, tree-by-tree records showed that most forests had acted as a carbon sink for most of the last 30 years, with tree growth exceeding mortality.

“When the 2015–2016 El Niño hit, the sink shut down. This was because tree death increased with the heat and drought,” according to the study.

“Here in the southeastern Amazon on the edge of the rainforest, the trees may have now switched from storing carbon to emitting it. While tree growth rates resisted the higher temperatures, tree mortality jumped when this climate extreme hit,” said Professor Beatriz Marimon, of Brazil’s Mato Grosso State University.

Hotter, drier

Of the 123 plots studied, 119 of them experienced an average monthly temperature increase of 0.5 degrees Celsius. Ninety-nine of the plots also suffered water deficits. Where it was hotter, it was also drier.

Prior to El Niño, the researchers calculated that the plots were storing and sequestering around one-third of a tonne of carbon per hectare per year. This declined to zero with the hotter and drier El Niño conditions.

The change was due to biomass being lost through the death of trees.

The greatest relative impact of the El Niño event was in forests where the long-term climate was already relatively dry, according to the researchers.

The researchers expected wetter forests to be most vulnerable to the extreme drier weather, as they would be least adapted to such conditions.

It turned out the opposite was true. Instead, those forests more used to a drier climate at the dry periphery of the tropical forest biome turned out to be most vulnerable to drought.

This suggested some trees were already operating at the limits of tolerable conditions.

‘Keep forests standing’

“The full 30-year perspective that our diverse team provides shows that this El Niño had no worse effect on intact forests than earlier droughts. Yet this was the hottest drought ever,” Professor Oliver Phillips, an ecologist at the University of Leeds who supervised the research and leads the global ForestPlots initiative.

“Where tree mortality increased was in the drier areas on the Amazon periphery where forests were already fragmented. Knowing these risks, conservationists and resource managers can take steps to protect them.”

“Through the complex dynamics that happen in forest environments, land clearance makes the environment drier and hotter, further stressing the remaining trees.

“So, the big challenge is to keep forests standing in the first place. If we can do that, then our on-the-ground evidence shows they can continue to help lock up carbon and slow climate change.”