HQ Team

September 3, 2023: The jury is still out on which virus causes chronic fatigue syndrome, its diagnosis, the treatment options, and even its very terminology.

Molecular biologists at the Cornell University revisited the syndrome, which is also known as myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) and found it may be triggered by viral infections. The illness affects about 67 million people globally.

The syndrome is defined under an umbrella of disabling symptoms that include muscle pain (myalgia) and effects on the brain (encephalo), spinal cord (myel), and inflammation (itis) – myalgic encephalomyelitis.

The Cornell study identified the possibility of the syndrome being caused by enteroviruses.

Etymology

The ME designation originated following an outbreak at London’s Royal Free Hospital in 1955. More than 200 members of the hospital staff became disabled, according to the study.

Melvin Ramsay, a consultant physician at the hospital coined “ME” based on its predominant symptoms.

In 1987, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) convened an extramural committee to change the name to “chronic fatigue syndrome” in 1988.

Because the CDC name trivializes the serious nature of the disease, the patient community and many medical professionals preferred ME, which continues to be widely used in the United Kingdom and Europe.

In 2015, a US Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee recommended yet another name, Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease, which has been largely ignored.

Unrefreshing sleep

According to the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, symptoms include a substantial reduction or impairment in the ability to engage in pre-illness levels of activity — occupational, educational, social, or personal life.

These last for more than six months.

The patients will also have post-exertional malaise after physical, mental, or emotional exertion that would not have caused a problem before the illness. They develop unrefreshing sleep.

Cognitive functions — thinking, memory, information processing, attention deficit and impaired psychomotor functions will be present.

Patients develop a worsening of symptoms upon assuming and maintaining upright posture. The orthostatic imbalance includes lightheadedness, fainting, increased fatigue, cognitive worsening, headaches, or nausea.

The CDC’s 2015 guidelines relied on the severity of the symptoms.

Enteroviruses

In her study, Maureen Hanson, a molecular biologist at Cornell, wrote that a particular group of viruses called enteroviruses might be the “most likely culprit” of ME.

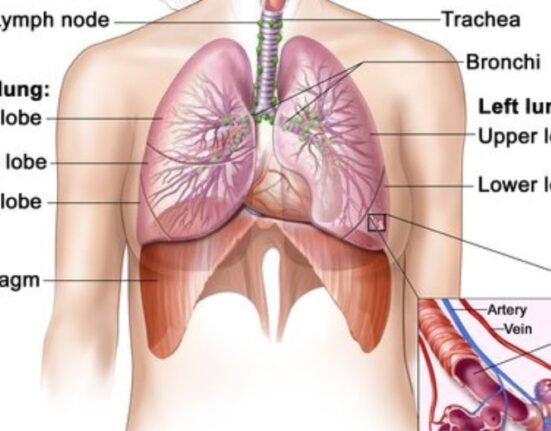

Enteroviruses are a group of RNA viruses that enter the body through the intestine. Their role in ME has been long suspected, but largely disputed.

Earlier studies have detected persistent enteroviral infections in people with ME/CFS. Over the years inconclusive results from studies comparing blood and tissue samples from people with ME/CFS to unaffected individuals deterred researchers from pursuing it further.

“Ignoring the abundant evidence for enterovirus (EV) involvement in ME/CFS has slowed research into the possible dire but hidden consequences of EV infections, including persistence in virus reservoirs,” Ms Hanson wrote in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

The causes for developing the condition have gone unidentified since 1930 — when it was first discovered.

Antibodies from prior infections

Finding a viral culprit for ME/CFS is tricky because blood tests can only point to a specific virus during the acute phase of infection.

After that, they will be full of the antibodies a person’s body has raised against all sorts of viruses from past infections.

Before SARS-CoV-2 emerged, the ability of RNA viruses to persist in tissues for long periods “was largely ignored,” she wrote.

Various studies in Australia, Norway and the US have pointed to different viruses such as Epstein–Barr virus infection, Q fever (caused by Coxiella burnetii), or Ross River virus infections, contributing to ME/CFS.

“History offers persuasive evidence to suspect the enterovirus family of causing ME/CFS. Both circumstantial and direct evidence exists to support such a conclusion, she wrote.

With the growing recognition of post-viral illnesses, researchers have looked anew at the link between viral infections and conditions such as ME/CFS.

Asymptomatic

By the time a person develops ME/CFS and receives a formal diagnosis — if they do — they or their treating doctor might not make the connection between their illness and a previous viral infection.

About half of enteroviral infections are asymptomatic, and people with ME/CFS who participate in research studies have likely been unwell for years. Enteroviruses are also very common and often cause mild illness.

Genetic sampling techniques might be better able to detect low amounts of residual virus hiding out in cells and tissues, and help figure out which viruses are possibly involved, Ms Hanson wrote.

Other viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus, are also thought to trigger ME/CFS. Like other human herpes viruses, Epstein-Barr virus can hide out in the body, evading the immune system for years until stress or some other illness reactivates the virus.

Malfunctioning mitochondria, the energy factories of our cells, and low levels of two key thyroid hormones have recently been implicated in ME/CFS – along with a host of genetic variants that a lot of people with the condition seem to have.

Do hidden reservoirs harbour these viruses? Have they induced autoimmunity through molecular mimicry? Is it a past or current infection that has resulted in the many findings of immune dysfunction in ME/CFS? Ms Hanson wrote.