HQ Team

October 11, 2022: Developing highly effective and durable vaccines against the human malaria parasites Plasmodium falciparum and P. vivax is a key priority for the world. Last year, the World Health Organisation gave the historic go-ahead for the first vaccine – developed by pharmaceutical giant GSK – to be used in Africa. Now, scientists at the University of Oxford have announced another groundbreaking malaria vaccine.

The team expects it to be rolled out next year after trials showed up to 80% protection against the deadly disease. Trial results from 409 children in Nanoro, Burkina Faso, have been published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases. It shows three initial doses followed by a booster a year later, give up to 80% protection.

The approval process has already been initiated, though results are still awaited from a larger trial of 4,800 children.

“We think these data are the best data yet in the field with any malaria vaccine,” said Prof Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute at the university

The WHO-approved vaccine, known as RTS,S has around 70% efficacy. Also, surprisingly there are some claims of the vaccine not being cost-effective and logistics problems in its dispensation as it requires four doses for it to be effective.

The Oxford scientists say their vaccine is cheap, and they already have a deal to manufacture more than 100 million doses yearly. The world’s largest vaccine manufacturer – the Serum Institute of India, has been chosen to manufacture the vaccine.

The charity Malaria No More said recent progress meant children dying from malaria could end “in our lifetimes”.

Malaria is endemic to most tropical countries and is an ongoing active threat in 85 countries and territories. The sub-Saharan region is most susceptible to the disease, with nearly 93% malaria death occurring here, with children below 5 accounting for 80 % of all malaria deaths.

Prof Hill said the vaccine – called R21 – could be made for “a few dollars” and “we really could be looking at a very substantial reduction in that horrendous burden of malaria”.

He added: “We hope that this will be deployed and available and saving lives, certainly by the end of next year.”

Professor Katie Ewer told the BBC it was “incredibly gratifying” to get this far and “the potential achievement that this vaccine could have if it’s rolled out could be really world-changing”.

Malaria vaccine progress and hurdles

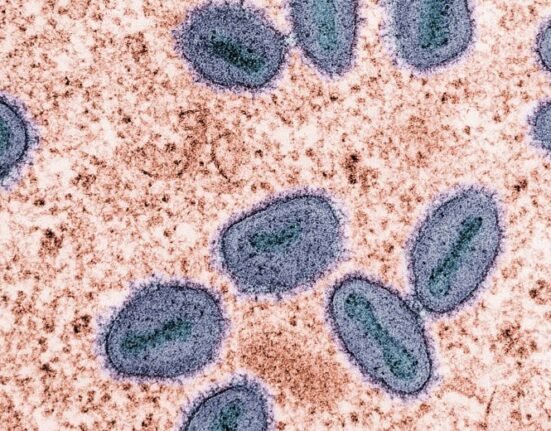

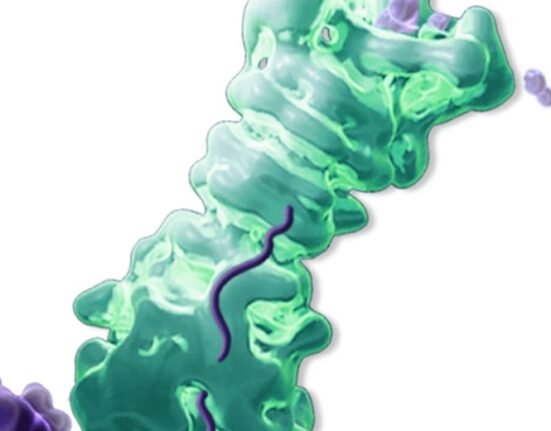

The Oxford vaccine is similar to the currently approved vaccine – made by GSK. Both are recombinants and target the first stage of the parasite’s lifecycle.

The vaccines are built using a combination of proteins from the malaria parasite and the hepatitis B virus, but Oxford’s version has a higher proportion of malaria proteins. The team think this helps the immune system to focus on malaria rather than hepatitis.

The initial success of the GSK vaccine and its large-scale real-life testing and effectiveness has made the Oxford team optimistic about the feasibility of manufacturing the current one.

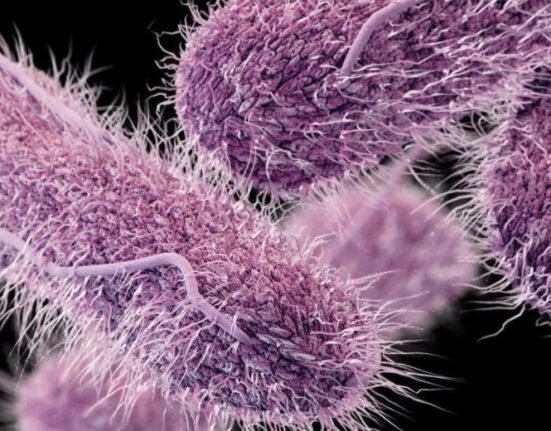

However, the RTS,S vaccine has not had a smooth sailing in Africa. One objection is its relative cost, which is estimated at $5 per dose. Another negative strike is that its efficacy goes down to around 30% in the face of severe bouts of malaria. Malaria is a complex disease to combat as the malaria parasite has thousands more genes than a virus and requires a multi-pronged attack.

Mosquito nets and antimalarial medicines, along with vaccination, have proven to be most effective in terms of logistics, money and efficacy in preventing deaths.

Lessons for the future

Malaria’s varied forms are impossible to tackle due to its ability to trick the human immune response and its sophisticated life cycle. What seems to be most effective in its eradication is scaling up the national-level distribution of insecticide-treated nets, finding feasible operational ways to reach the remotest vulnerable communities, and being consistent with the reach of medicines and vaccines. This combined effort has proven to be effective in saving millions of lives