HQ Team

August 7, 2023: A new genetic variant of HIV infection, discovered after more than 25 years of research and linked to lower infection rates among people with African ancestry, may help direct future treatment of the virus, according to global researchers.

The relationship between human DNA and HIV comes from studies among European populations, mostly. Given that HIV disproportionately affects people on the African continent, it’s important to understand the role of genetics in HIV infection in African populations.

More than 25 million people have tested HIV-positive from the African continent.

“African populations are still drastically underrepresented in human DNA studies, despite experiencing the highest burden of HIV infection,” said Paul McLaren from the Public Health Agency of Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory and joint first author.

Lower viral loads

“By studying a large sample of people of African ancestry, we’ve been able to identify a new genetic variant that only exists in this population and which is linked to lower HIV viral loads.”

Viral load is the amount of a virus in a patient’s system.

Higher levels are known to correlate with faster disease progression and increased risk of transmission. Viral load varies widely among infected individuals and is influenced by a number of factors including an individual’s genetic makeup.

Researchers analysed the DNA of almost 4,000 people of African ancestry living with HIV-1, the most common type of the virus.

They identified a variant within a region on chromosome 1 containing the gene CHD1L which was associated with reduced viral load in carriers of the variant. Between 4% and 13 % of people of African origin are thought to carry this particular variant.

Repairs damaged DNA

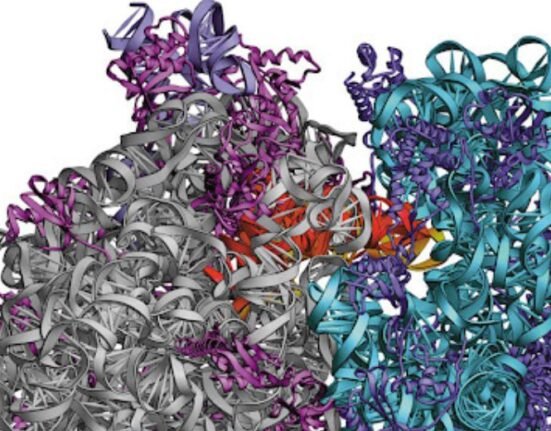

CHD1L is known to play a role in repairing damaged DNA, though it is not clear why the variant should be important in reducing viral load, according to the researchers.

As HIV attacks immune cells, researchers at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Medicine, led by Dr Harriet Groom and Professor Andrew Lever, used stem cells to generate variants of cells that HIV can infect in which CHD1L had either been switched off or its activity turned down.

HIV turned out to replicate better in a type of immune cell known as a macrophage when CHD1L was switched off.

In another cell type, the T-cell, there was no effect, perhaps surprising since most HIV replication occurs in the latter cell type.

“This gene seems to be important to controlling viral load in people of African ancestry,” Dr Groom said.

Controlling replication

“Although we don’t yet know how it’s doing this, every time we discover something new about HIV control, we learn something new about the virus and something new about the cell. The link between HIV replication in macrophages and viral load is particularly interesting and unexpected.”

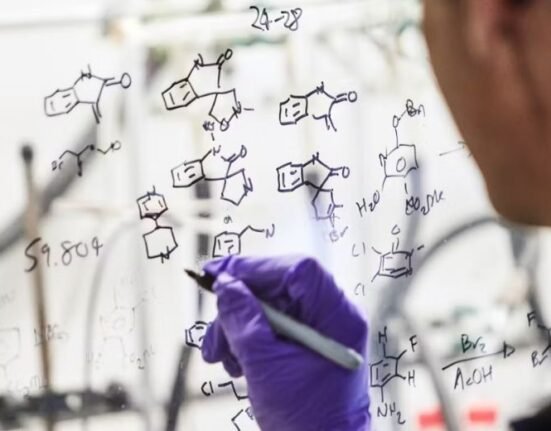

Co-author Professor Manjinder Sandhu from the Faculty of Medicine at Imperial College London said the next step was to fully understand exactly how this genetic variant controls HIV replication.

According to UNAIDS, there were 39 million people living with HIV globally in 2022.

A combination of pre-exposure drugs and medicines that dramatically reduce viral loads has had a major impact on transmission, yet 1.3 million people were newly infected in 2021.

While treatments have improved dramatically since the virus was first identified, 630,000 people still died from AIDS-related illnesses in 2022.

The findings were published in the Nature, a British weekly scientific journal.

7 Comments