HQ Team

October 30, 2025: For millions of people with severe liver disease, a transplant is the only hope. Now a new discovery that makes therapeutic cells “sticky” could soon provide a powerful, less invasive alternative.

Scientists at the University of Birmingham, in collaboration with InSphero AG, Switzerland, have developed a novel method to supercharge a promising cell therapy for liver disease. The technique involves coating repair cells with natural sugars, dramatically improving their ability to stick to and regenerate damaged liver tissue.

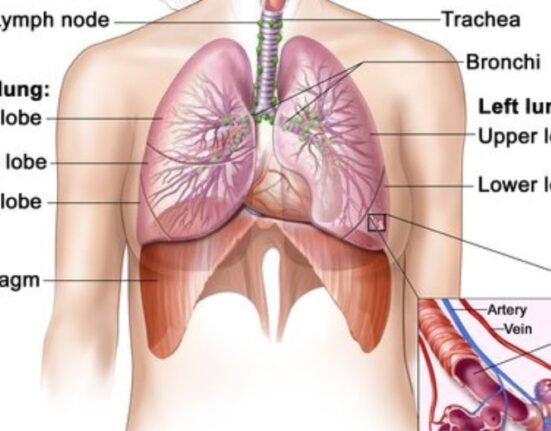

This advancement is significant because liver disease is a massive global health burden, causing over two million deaths annually worldwide. While liver transplantation is the current last-resort treatment, it is plagued by a critical shortage of donor organs and high risks.

Slippery Cells

A promising alternative to transplants involves using hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs), a type of stem cell that can turn into new liver cells. The major hurdle has been getting these therapeutic cells to stay in place.

“When introduced into the body, they often don’t bind well to the existing liver tissue, making treatment less effective,” explains the new research. The cells would simply wash away before they could do their job.

Solution: a sweet and sticky coating

The research team devised an elegant solution: give the cells a temporary sugar coat. Using a technique called metabolic oligosaccharide engineering (MOE), they coated HPCs with natural polysaccharides like hyaluronic acid and alginate.

This “sweet and sticky” coating supercharged the cells’ adhesion without genetic modification, a key safety advantage.

“We’ve given these cells a temporary adhesive coating, like a natural biological glue,” said lead author Dr. Maria Chiara Arno from the University of Birmingham. “It helps them latch onto the damaged liver and start the repair process.” The coating is temporary, lasting just long enough for the cells to settle in before naturally breaking down.

Promising results

The results, published in Communications Biology, were striking. In lab tests mimicking human body conditions, the sugar-coated cells showed a significant increase in their ability to stick to liver microtissues and blood vessel cells compared to uncoated cells -7.

The coated cells not only stuck better but also began spreading out and forming structures that help them anchor and communicate with their new environment. Importantly, the coating did not harm the cells or prevent them from maturing into functional liver cells capable of producing vital proteins.

Liver disease

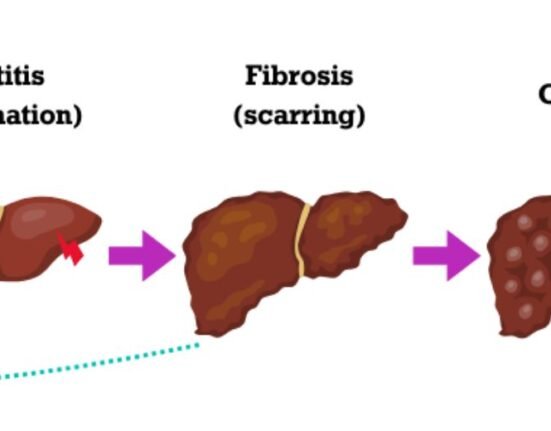

This discovery comes at a critical time. The field of cell therapy for liver disorders is rapidly evolving, with Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) being hailed as a potential “game-changer” for their ability to reduce inflammation, fight fibrosis, and regenerate tissue .

The Birmingham team’s approach directly addresses one of the biggest challenges in making these therapies work: ensuring the healing cells engraft and survive in the target organ.

“Liver transplants are the only option for many severe liver diseases, but there aren’t enough donor livers available,” said Dr. Arno. “This new method could provide an alternative by making cell therapy more effective, potentially helping many people with liver disease” .

The researchers believe this sugar-coating method could be adapted for other cell types used to treat a range of diseases. The next steps will involve further studies to explore the long-term impact of this technique on cell health and the body’s immune response .

With its innovative approach to a longstanding problem, this “sticky cell” technology represents a significant step toward a future where a failing liver can be healed not by replacement, but by repair.