HQ Team

May 20, 2023: A recent study conducted by researchers at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden has shed further light on how the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) can trigger multiple sclerosis (MS) or contribute to the progression of the disease.

The study, published in Science Advances, reveals that certain individuals with MS have antibodies that mistakenly attack a protein in the brain and spinal cord, which can lead to MS symptoms.

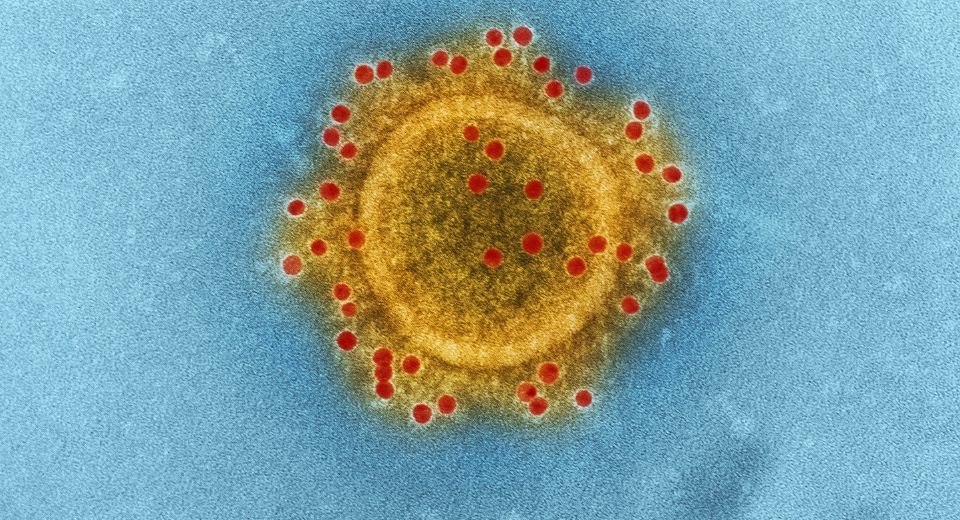

The Epstein-Barr virus is one of the nine known human herpesvirus types in the herpes family and is one of the most common viruses in humans. It commonly infects individuals during early life and typically remains dormant in the body without causing any symptoms. However, it has been linked to the development and progression of MS.

The study findings demonstrate that approximately 23% of MS patients possess antibodies against EBV that erroneously target a protein in the central nervous system, which results in MS symptoms. This highlights the role that EBV antibodies play the pathogenesis of MS.

Earler studies have established the link between EBV and multiple sclerosis (MS) but its exact role in the progression of the disease is not clear.

Last year, two papers published in Science and Nature suggested that EBV infection precedes MS and that antibodies against the virus may be involved. But its molecular mechanism remained unclear.

“MS is an incredibly complex disease, but our study provides an important piece in the puzzle and could explain why some people develop the disease,” says Olivia Thomas, postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet and shared first author of the paper.

“We have discovered that certain antibodies against the Epstein-Barr virus, which would normally fight the infection, can mistakenly target the brain and spinal cord and cause damage.”

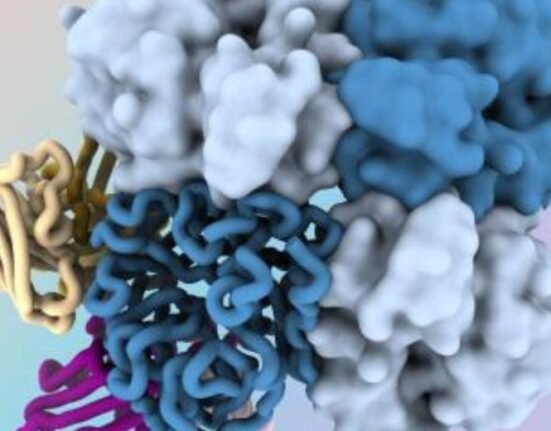

Misdirected antibodies

For their study, the researchers analyzed blood samples from more than 700 patients with MS and 700 healthy individuals. They discovered that antibodies that bind to a certain protein in the Epstein-Barr virus, EBNA1, can also bind to a similar protein in the brain and spinal cord called CRYAB, whose role is to prevent protein aggregation during conditions of cellular stress such as inflammation. The antibodies were present in about 23 percent of MS patients and 7 percent of control individuals.

These misdirected antibodies can damage the nervous system and cause severe symptoms in MS patients, including problems with balance, mobility and fatigue.

“This shows that, whilst these antibody responses are not required for disease development, they may be involved in disease in up to a quarter of MS patients,” says Olivia Thomas.

“This also demonstrates the high variation between patients, highlighting the need for personalized therapies. Current therapies are effective at reducing relapses in MS, but unfortunately, none can prevent disease progression.”

T-cells cross-reactivity

The researchers also found a similar cross-reactivity among T cells of the immune system.

“We are now expanding our research to investigate how T cells fight EBV infection and how these immune cells may damage the nervous system in multiple sclerosis and contribute to disease progression,” says Mattias Bronge, affiliated researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet and shared first author of the paper.

These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence linking EBV to MS and provide valuable insights into the complex relationship between viral infections and autoimmune diseases. Continued research in this area may pave the way for novel therapeutic approaches in the future.

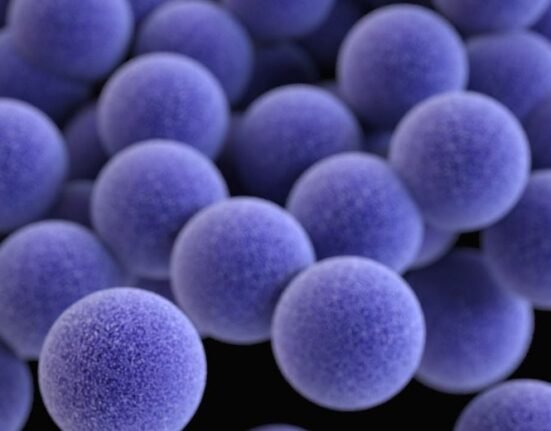

Multiple Sclerosis

Over 2.8 million people around the world suffer from MS, an autoimmune disease in which the immune system damages the brain and spinal cord.

Symptoms include fatigue, vision disturbance, problems with mobility and balance and cognitive dysfunction. Many people who develop MS experience symptoms followed by a period of recovery, but over time the disease can progress to permanent disability.