HQ Team

February 22, 2024: Eating tuna may expose humans to methylmercury, a toxic chemical that affects the central nervous system, and the compound’s toxicity level in the fish has stagnated for the last 53 years, according to a study.

The protein-rich fish, one of the most popular seafood, feed on contaminated smaller fish and crustaceans and levels of methylmercury in their muscles have remained the same since 1971.

French researchers led by Anne Lorrain, Anaïs Médieu, who holds a PostDoc position at the La Rochelle University, Toulouse, France and David Point worked with an international team of researchers to investigate the trends of mercury in tuna over the past 50 years.

Environmental protection policies have helped reduce mercury pollution from human activities like burning coal and mining worldwide, the researchers posted in a statement on the American Chemical Society’s website.

“However, people can still be exposed to methylmercury, and unborn babies and young children are at highest risk of harm.”

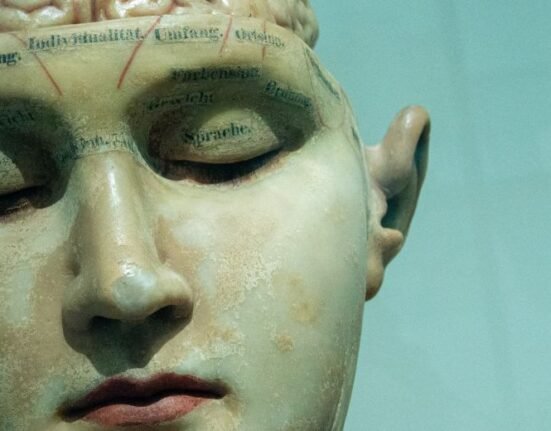

Most poisonous mercury compound

Methylmercury is a toxic chemical that affects the nervous system and is possibly the primary form of mercury in tuna contamination. It is known to be the most poisonous among the mercury compounds and is created when inorganic mercury circulating in the general environment is dissolved into freshwater and seawater. It is known to become condensed through the ecological food chain and ingested by humans.

Nearly all fish and shellfish contain trace amounts of methylmercury.

The researchers set out to determine whether lower atmospheric emissions resulted in lower concentrations of mercury in the oceans, specifically the methylmercury found in food sources that sit at the top of the food chain like tuna.

They also wanted to simulate the impact of different environmental policies on oceanic and tuna mercury levels in the future.

3,000 tuna muscle samples

The researchers compiled previously published data and their data on total mercury levels from nearly 3,000 tuna muscle samples of fish caught in the Pacific, Atlantic and Indian Oceans from 1971 to 2022. Over the same period airborne mercury decreased globally.

They specifically looked at tropical tuna — skipjack, bigeye and yellowfin. These three species account for 94% of global tuna catches. Because they don’t undergo transoceanic migrations, any contamination found in the animals’ muscles likely reflects the waters they swim in.

The researchers concluded that the static levels in tuna may be caused by the upward mixing of “legacy” mercury from deeper in the ocean water into the shallower depths where tropical tuna swim and feed.

The legacy mercury could have been emitted years or even decades prior and doesn’t yet reflect the effects of decreasing emissions in the air.

The team’s mathematical models predicted even the most restrictive emission policy would take 10 to 25 years to influence oceanic mercury concentrations, and then drops in tuna would follow decades later.

The researchers stated that their forecasting did not consider all variables in tuna ecology or marine biogeochemistry.

Their findings point to a need for an aggressive global effort to reduce mercury emissions and a commitment to long-term and continuous mercury monitoring in ocean life.