By Aparna S

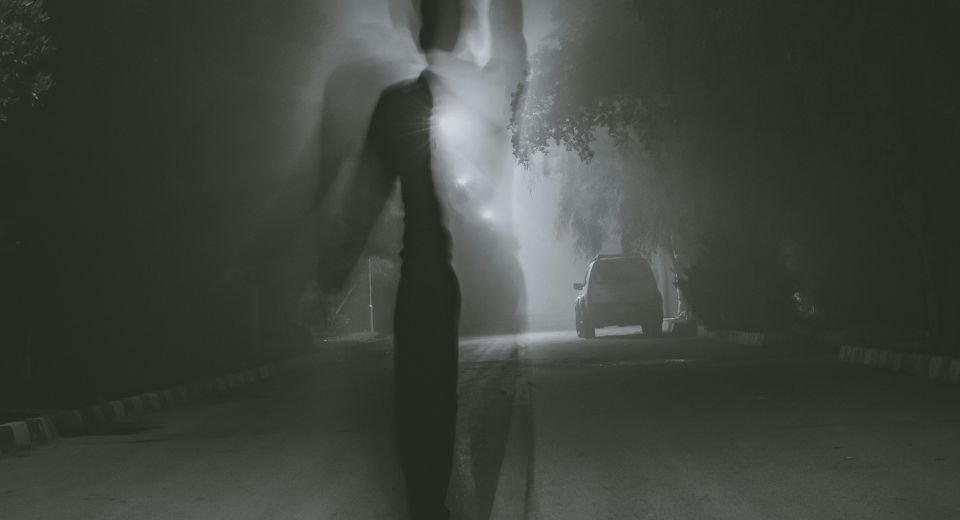

June 19, 2025: In the 1990s, no vacation was considered complete without the obligatory ghost story session. Every cousin, uncle, or aunt had a tale to share, each infused with the unique flavour and flair of the region. Among these eerie narratives was the story of Panayattil Pankajakshi, a haunting figure recounted during post-dinner power outages.

She embodied the archetypal tragic female ghost of Kerala state in southern India—a wronged, underprivileged village maiden.

Pankajakshi belonged to a poverty-stricken family and was unfortunate enough to attract the unwanted carnal attention of a local aristocrat, which she steadfastly rejected. What followed was a familiar tragedy. Her lifeless body was found floating in a lake called Malummel Kayal. Since then, she has been said to haunt not only deserted roads and the tops of palm trees but also the bedtime stories told to young children.

While the political correctness of narrating such a tale to a third-grade student is questionable, one cannot help but be captivated by the bewitching embodiment of voluptuous beauty represented by the Yakshi.

A complex symbolism

Beneath the surface of myth, the Yakshi’s seductive yet bloodthirsty allure carries deeper significance. In Kerala, the Yakshi is more than a mere seductress. She possesses the power to both curse and cure. Many Hindu temples revere her as a goddess of women, children, cattle, and the natural world. Early Buddhist and Jain traditions honour her as a goddess of fertility, sensuality, and abundance.

However, throughout history, the myth of the Yakshi in the collective psyche of southern India underwent a sinister transformation. Emerging from a tragic past marked by betrayal, sexual violence, and unjust death, she became a seductive vampire who lures men to their demise.

This cultural iconography—depicted in Aitihyamala (a compendium of Indian mythological legends, magicians, feudal rulers, poets, and ghosts), temple scriptures, and ritual performances such as Theyyam and Padayani—evokes both fear and fascination.

Unlike the conventional bloodthirsty vampire, the Yakshi embodies a collective confirmation of female agency and sexuality, especially within a culture where women’s autonomy was strictly policed.

In a society deeply shaped by patriarchal morality, female identity was constrained to two archetypes: the idealised maternal figure or the dangerous demoness. From this repression, the concept of the Yakshi emerges as the disowned desire of the male psyche and the culturally suppressed female rendered monstrous.

A Jungian interpretation

Carl Gustav Jung, the Swiss psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology, introduced concepts such as the collective unconscious, animus, and anima. The collective unconscious refers to a shared, inherited layer of the unconscious mind common to all humans, containing archetypes—universal, innate symbolic representations of fundamental human experiences. Jung posited that this collective unconscious shapes our ways of thinking and behaving, suggesting that we inherit a shared human consciousness filled with deep-seated patterns and symbols.

In Jungian psychology, the Yakshi represents the female archetype. The anima is the unconscious feminine image within a man. When man projects this unconscious perspective onto nature, art, or culture, he is engaging with a powerful inner force. Positively, this can foster creativity and healthy psychic integration. However, when repressed or mismanaged, it becomes distorted, manifesting as the seductive destroyer, a classic projection of the dark anima: the Yakshi.

Men haunted by a Yakshi are not victims of a supernatural encounter. They are confronting disowned parts of themselves. The Yakshi’s irresistible beauty reflects their desire, while her terrifying, bloodthirsty violence symbolises their guilt and fear of unacceptable desires.

This duality also echoes an ancient concept of the divine feminine, where goddesses were powerful and ambivalent rather than merely docile and loving. Perhaps the Yakshi is the last echo of a once-autonomous female deity, degraded into a ghost by patriarchal reinterpretation aligned with post-Brahmanical cultural norms.

The Yakshi as a path to healing

From this perspective, the Yakshi’s dual identity symbolises a dissociated aspect of culture itself—a manifestation of what society has yet to integrate or mourn. True healing arises not from suppressing these shadow elements but from their integration. To banish, fear, or exorcise the Yakshi is to remain trapped in a fragmented psyche.

The real journey toward individuation involves confronting her and acknowledging her conflicting duality as an intrinsic part of the human experience.

The Yakshi is not the conclusion of a story but a threshold between the conscious and unconscious, the rational and irrational, the civilised and the wild. She demands attention—not as a villain, but as a guide.