HQ Team

March 5, 2025: US scientists have blocked a protein that kills a variety of cancer cells in an experiment on mice, pointing to a new potential target for cancer treatment, according to the National Institutes of Health.

Scientists found that, when deprived of amino acids, cancer cells cooperated to extract and share them from their environment. Blocking a protein called CNDP2 stopped this cooperative survival strategy, according to a statement from NHS.

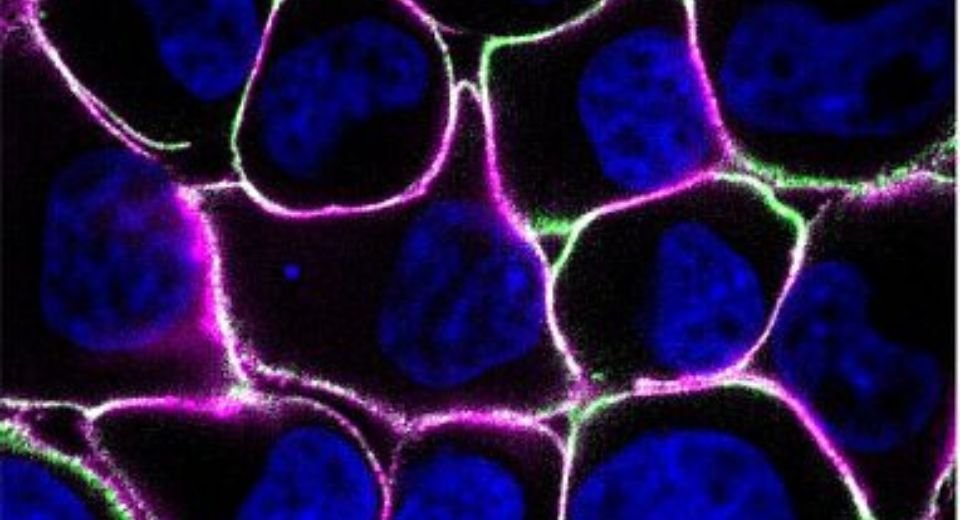

Cancer cells, which can grow and divide rapidly, often compete with each other and surrounding normal cells for nutrients, oxygen, and other substances.

Studies have suggested that cells in tumours may sometimes need to cooperate to survive. A better understanding of how cancer cells cooperate could provide new targets for treatments. However, this aspect of tumour growth has not been studied in depth.

Allee effect

During the research, partly funded by the NIH, the scientists probed a peculiar characteristic of cell growth called the Allee effect, where the viability of a cell population drops below a certain cell density. This hinted that cells are somehow cooperating to survive.

The researchers grew several types of cancer cells with various restricted nutrients. They found that depriving the cells of an amino acid that the cells need to grow appeared to create an Allee effect. Only higher-density cell populations survived under these conditions. This indicated that a cooperative survival strategy had kicked in.

To look at whether cancer cells exhibit an Allee effect, the team then further explored how cancer cells might be cooperating to survive in low-amino acid environments.

Chains of amino acids called oligopeptides can be broken down by cells into individual amino acids. The scientists found that cancer cells released substances into their immediate environment that broke nearby oligopeptides down.

Because this occurred outside the cancer cells, any cell in the immediate vicinity could use the resulting free amino acids.

Oligopeptides

Taking a step further, scientists found that a single enzyme called CNDP2 was needed to extract the amino acids from oligopeptides. When the researchers blocked CNDP2 activity in a variety of cancer cell types, the cells could no longer break down oligopeptides, and the populations died.

The team next tested whether blocking CNDP2 could slow or stop tumour growth in living animals. They implanted mice with a type of lung cancer cell known to be sensitive to amino acid deprivation and fed the mice a diet designed to reduce circulating levels of these nutrients.

Mice injected with a drug called bestatin, which blocks CNDP2, had substantially smaller tumours than mice injected with an inactive control compound.

“Dramatic results” were seen when the team used techniques to delete the gene that produces CNDP2 from cancer cells.

No observable tumours

When fed the special diet, a significant number of the mice injected with these cells didn’t develop observable tumours. These results suggest that inhibiting CNDP2 may be a promising therapeutic approach for cancer types sensitive to amino acid deprivation.

“Competition is still critical for tumour evolution and cancer progression, but our study suggests that cooperative interactions within tumours are also important,” said Dr Carlos Carmona-Fontaine from New York University Carmona-Fontaine, who led the team.

“Thinking about (these) mechanisms that tumour cells exploit can inform future therapies.”