HQ Team

November 23, 2022: Patients living with HIV are at an increased risk of developing chronic inflammation due to “immunologic memory,” according to a study.

The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) attacks the body’s immune system. Patients often are in danger of suffering from cardiovascular disease and other comorbidities, a study by researchers from George Washington University stated.

An HIV protein permanently alters immune cells in a way that causes them to overreact to other pathogens, which are organisms causing the disease to their host.

A human immunodeficiency virus type 1 encodes 15 distinct proteins.

Gene expressed

When the protein infects immune cells, genes in those cells associated with inflammation turn on or become expressed, according to the study.

These pro-inflammatory genes remain expressed even when the HIV protein is no longer in the cells.

HIV patients risk prolonged inflamation due to this “immunologic memory” of the initial HIV infection. They also stand a chance of developing cardiovascular disease and other comorbidities.

If HIV is untreated, it can lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Presently, there is no cure. Once people get HIV, they have it for life. Proper medical care and antiretroviral therapy can control HIV.

No risk elimination

“This research highlights the importance of physicians and patients recognising that suppressing or even eliminating HIV does not eliminate the risk of these dangerous comorbidities,” said Michael Bukrinsky, lead author of the study.

“Patients and their doctors should still discuss ways to reduce inflammation, and researchers should continue pursuing potential therapeutic targets that can reduce inflammation and comorbidities in HIV-infected patients.”

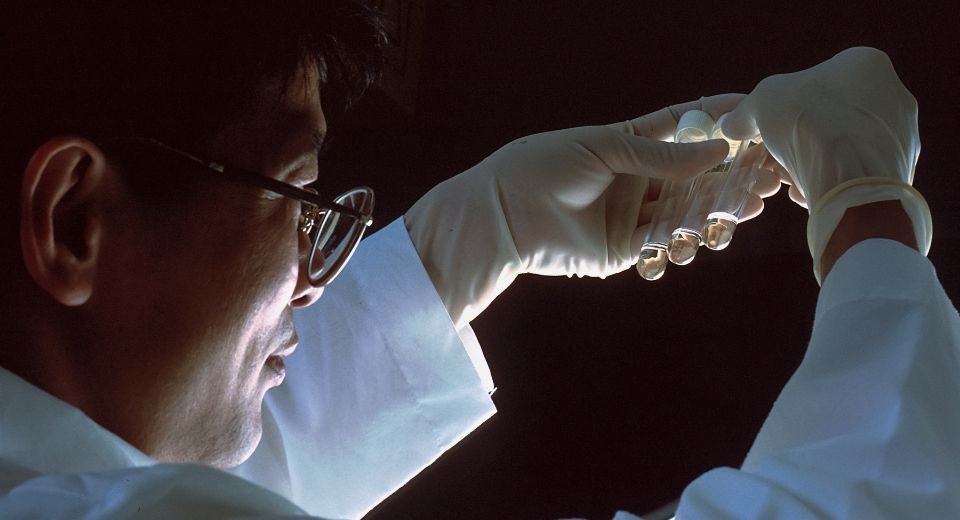

For the study, the research team isolated human immune cells in vitro and exposed them to the HIV protein Nef.

The amount of Nef introduced to the cells is similar to that found in about half of HIV-infected people taking antiretrovirals whose HIV load is undetectable.

The researchers then introduced a bacterial toxin to generate an immune response from the Nef-exposed cells.

“Compared to cells that were not exposed to the HIV protein, the Nef-exposed cells produced an elevated level of inflammatory proteins, called cytokines,” according to the study.

When the team compared the genes of the Nef-exposed cells with those not exposed to Nef, they identified pro-inflammatory genes that were ready to be expressed due to Nef exposure.

The findings in this study could help explain why specific comorbidities persist following other viral infections, including COVID-19, Bukrinsky said.