HQ Team

May 22, 2023: A combination of flesh-eating bacteria, brown seaweed, and plastics in the ocean can potentially create a “pathogen storm” affecting both marine life and public health, according to researchers from Florida Atlantic University.

Vibrio vulnificus bacteria, found in waters globally, are the dominant cause of death in humans from the marine environment.

It causes life-threatening food-borne illnesses resulting from seafood consumption as well as disease and death from open wound infections, according to the study.

Plastic marine debris, first found in surface waters of the Sargasso Sea, has become a worldwide concern, and is known to persist decades longer than natural substrates in the marine environment.

The Sargasso Sea has no land boundaries. It is distinguished from other parts of the Atlantic Ocean by its characteristic brown Sargassum seaweed and often calm blue water.

Macroalga

For more than a decade Sargassum’s brown macroalga has been rapidly expanding in the sea, located in the North Atlantic Ocean.

The algae has expanded to other parts of the open ocean such as the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt, including frequent and unprecedented seaweed accumulation events on the beaches.

The sea harbors species of Sargassum that are ‘holopelagic’ — which means that the algae not only freely float around the ocean but reproduces vegetatively on the high seas.

The ecological relationship of vibrios with Sargassum algae is unclear, and genomic and metagenomic evidence has been lacking as to whether vibrios colonizing plastic marine debris and Sargassum spp. could potentially infect humans.

16 Vibrio cultivars

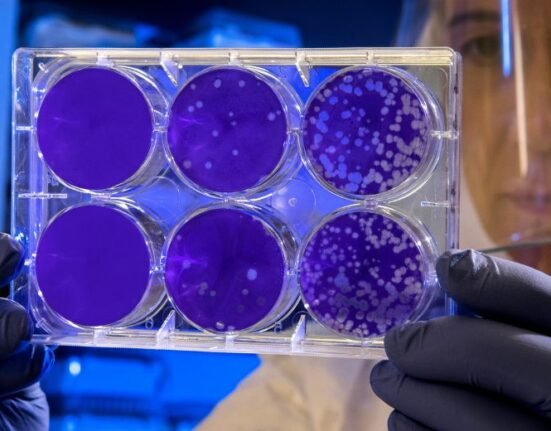

Researchers fully sequenced the genomes of 16 Vibrio cultivars isolated from eel larvae, plastic marine debris, seaweeds, and seawater samples collected from the Caribbean and Sargasso seas of the North Atlantic Ocean.

They discovered that Vibrio pathogens could stick to microplastics and these microbes might be adapting to plastic.

“Plastic is a new element that’s been introduced into marine environments and has only been around for about 50 years,” said Tracy Mincer, Ph.D., corresponding lead author and an assistant professor of biology at FAU’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute and Harriet L. Wilkes Honors College.

“Our lab work showed that these Vibrio is extremely aggressive and can seek out and stick to plastic within minutes. We also found that there are attachment factors that microbes use to stick to plastics, and pathogens use the same kind of mechanism.”

Undescribed microbe group

The study, published in the journal Water Research stated that open ocean vibrios represent an up-to-now undescribed group of microbes.

Some of them represent a potential new species, possessing a blend of pathogenic and low nutrient acquisition genes, reflecting their pelagic habitat (an imaginary water column that exists between the surface of the sea to the bottom), and the substrates and hosts they colonize.

The genes are closely related to cholera and non-cholera bacterial strains. Researchers also discovered that zonula occludens toxin or “zot” genes, first found in Vibro cholerae, were retained in the Vibrios they found.

These genes secreted a toxin that increases intestinal permeability.

“Another interesting thing we discovered is a set of genes called ‘zot’ genes, which causes the leaky gut syndrome,” said Mincer.

“For instance, if a fish eats a piece of plastic and gets infected by this Vibrio which then results in a leaky gut and diarrhea, it’s going to release waste nutrients such nitrogen and phosphate that could stimulate Sargassum growth and other surrounding organisms.”

Omnivorous lifestyle

Findings show that some Vibrio spp. in this environment have an ‘omnivorous’ lifestyle targeting both plant and animal hosts and an ability to persist in oligotrophic conditions.”

With increased human-Sargassum-plastic marine debris interactions, associated microbial flora of these substrates could harbor potent opportunistic pathogens.

“I don’t think at this point, anyone has considered these microbes and their capability to cause infections,” said Mincer.

“We want to make the public aware of these associated risks. In particular, caution should be exercised regarding the harvest and processing of Sargassum biomass until the risks are explored more thoroughly.”

Collaborators of the study included the NIOZ Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany.