HQ Team

March 14, 2023: A study on mice carried out by the Institute of Cancer Research, UK, found that a drug used to treat Leukaemia is able to stop the occurrence and spread of secondary breast cancer elsewhere in the body.

Dr Frances Turrell, a postdoctoral fellow at the Breast Cancer Research Centre, and colleagues induced oestrogen-receptor positive (ER+) breast cancer in mice. This is the most common type of breast cancer in humans, accounting for up to 80 per cent of cases, and usually occurs in people over the age of 50. ER+ can recur several years after successful treatment of cancer as undetected cells move to other parts of the body much before the treatment ensues. Says Turrell. “These cells essentially stay dormant and then something may trigger them to reawaken them.”

The researchers, for their experiment, gave young mice – aged 8 to 10 weeks – and older mice – aged 9 to 18 months – ER+ positive breast cancer. Nearly all had cancer cells at secondary sites after two to five weeks of being induced with cancer cells.

The researchers found that the young mice were able to withstand the cancer cells and suffered no division of these cells, but the older mice the cells were more susceptible to the development of tumours, which mainly grew in the animals’ lungs.

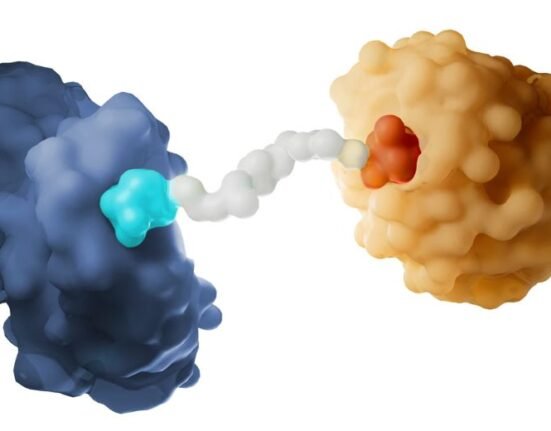

This tumour growth in the older mice was linked to the upregulation of a growth factor called PDGF-C in the lungs, which occurred less in the younger mice.

PDGF-C levels increase in the lungs with age in most animals, which likely triggers an environment that stimulates secondary cancer cells to divide, says Turrell.

According to Clare Isacke at the Institute of Cancer Research, higher PDGF-C levels may also be linked to a weaker immune system.

Inhibiting PDGF-C with drug Imatinib

The researchers then decided to use imatinib, a drug widely given to people with chronic myeloid leukaemia to inhibit PDGF-C that in turn promotes tumour growth.

Imatinib inhibited the growth rate of the mice’s secondary tumours, but some lesions did still form, says Turrell.

Although this treatment has potential, the researchers are still not sure of the side-effects of the treatment and how to predict whose ER+ breast cancer may later recur elsewhere in their body, reiterates Turrell.

There are many side effects of imatinib, according to Isacke. “You don’t want to be treating someone who won’t actually experience a relapse,” she says.

The researchers now plan to repeat this experiment in mice using a drug that has a more targeted effect on PDGF-C levels.

The full study can be accessed in the journal Nature, DOI: 10.1038/s43018-023-00525-y