HQ Team

November 29, 2023: The USFDA is probing cancer therapies of Gilead Sciences, Johnson & Johnson and Novartis following reports of malignancies in patients who received treatment.

“Although the overall benefits of these products continue to outweigh their potential risks for their approved uses, the FDA is investigating the identified risk of T cell malignancy with serious outcomes, including hospitalization and death, and is evaluating the need for regulatory action,” according to an FDA statement.

The therapies under the FDA scanner include Abecma and Breyanzi made by Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Biotech, Inc’s Carvykti, Novartis’ Kymriah, and Tecartus and Yescarta manufactured by Kite Pharma — acquired by Gilead Sciences in 2017.

The initial approvals of these products included post-marketing requirements to conduct 15-year long-term follow-up observational safety studies to assess the long-term safety and the risk of secondary malignancies occurring after treatment.

Life-long monitoring

“Patients and clinical trial participants receiving treatment with these products should be monitored life-long for new malignancies,” according to the statement.

Drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors are already in broad use to treat people with many types of cancer, including melanoma, lung, kidney, bladder, and lymphoma.

CAR T-cell therapies are not as widely used as immune checkpoint inhibitors, even though they have shown the same ability to eradicate very advanced leukaemia and lymphomas and to keep the cancer at bay for many years.

Since 2017, six CAR T-cell therapies have been approved by the FDA. All are approved for treating blood cancers, including lymphomas, some forms of leukaemia, and, most recently, multiple myeloma.

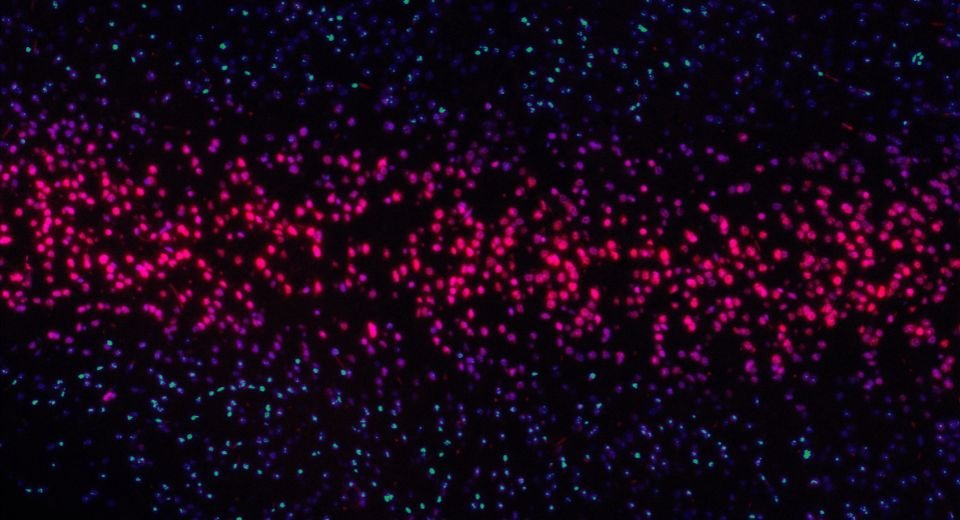

The USFDA had received reports of patients developing a type of T-cell blood cancer after being treated with genetically modified cells called chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies or CAR-T.

Kill cancer cells

CAR T cells are the equivalent of “giving patients a living drug,” said Renier J. Brentjens, MD, PhD, of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

T cells help orchestrate the immune response and directly kill cells infected by pathogens.

Currently, available CAR T-cell therapies are customised for each individual patient. They are made by collecting T cells from the patient and re-engineering them in the laboratory to produce proteins on their surface called chimeric antigen receptors, or CARs.

The CARs recognise and bind to specific proteins, or antigens, on the surface of cancer cells.

After the revamped T cells are “expanded” into the millions in the laboratory, they’re then infused back into the patient.

If all goes as planned, the CAR T cells will continue to multiply in the patient’s body and, with guidance from their engineered receptor, recognise and kill any cancer cells that harbour the target antigen on their surfaces.