HQ Team

December 10, 2022: A harmless beam of infrared light on a person’s finger or ear can detect malaria in five to ten seconds, researchers from the University of Queensland have found.

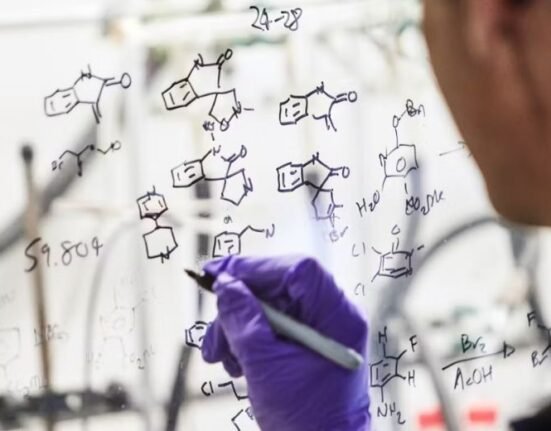

A blood test usually detects malaria, but this tool collects an infrared signature processed by a computer algorithm.

The device is smartphone-operated, so results are acquired in real-time.

To eliminate malaria, scalable, rapid, affordable tools and can detect patients with low parasitaemia is required. Non-invasive diagnostic tools that are rapid, reagent free and cheap would also be a justifiable platform for testing malaria in asymptomatic patients.

Non-invasive surveillance techniques for malaria remain a diagnostic gap, according to the researchers. Using a miniaturised hand-held near-infrared spectrometer, they read varying parasitaemia or a demonstrable presence of the level of parasites in the blood in less than 10 seconds.

Portable

The instrument is portable, can achieve results in real-time, and it can screen thousands of people in a day without consuming any reagents, a substance used for chemical analysis.

It is ideal for screening a large population as a surveillance tool to identify infected populations with minimal cost and time and can easily be scaled up.

The researchers said the biggest challenge in eliminating the disease is the presence of asymptomatic people in a population who act as a reservoir for transmission by mosquitos.

The World Health Organization has proposed large-scale surveillance in endemic areas. This affordable and rapid tool offers a way to achieve that, said Dr Maggy Lord of Queensland’s School of Biological Sciences and international team leader.

”The technology could also help tackle other diseases. We’ve successfully used this technology on mosquitoes to detect infections such as malaria, Zika and dengue non-invasively,” Dr Lord said.

“In our post-COVID world, it could be used to better tackle diseases as people move around the globe. We hope the tool could be used at ports of entry to screen travellers, minimising the re-introduction of diseases and reducing global outbreaks,” he said.

No reagent

“Currently, it’s incredibly challenging to test large groups of people, such as the population of a village or town – you have to take blood from everyone and mix it with a reagent to get a result,” he said.

In 2021, the WHO estimated 241 million malaria-related cases and 627,000 malaria-related deaths occurred in 2020. The plasmodium parasites which cause the disease are transmitted to people by bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

Most of the cases are in sub-Saharan Africa, where 90 per cent of deaths are children under five years old.

Towards the end of 2023 , millions of children living in areas of higher risk of illness and death from malaria are also expected to benefit from the life-saving impact of the world’s first malaria vaccine, RTS,S. Other malaria vaccines are in the product development pipeline, according to the WHO.

RTS, S is a recombinant protein-based malaria vaccine. In October 2021, the vaccine was endorsed by the World Health Organization for “broad use” in children, making it the first malaria vaccine candidate, and first vaccine to address parasitic infection, to receive this recommendation. It is being made by GSK Plc, in partnership with PATH, a Seattle-based nonprofit global health organization, and support from a network of African centres.

“It’s still early days, but this proof-of-concept is exciting,” Dr Lord said.